A day of restoration

With a focus on Indigenous People’s Day last weekend, the Hocak (Ho-Chunk) Nation and Sauk County joined together for three days of restoration, celebration, and commemoration.

Saturday’s Day of Restoration, saw citizens of Sauk County and the Hocak Nation come together, for a day of education that hopefully will become a catalyst for understanding, the areas indigenous culture, and forging closer relationships.

The prairie

On a crisp and windy morning at Maa Wakacak (Sacred Earth), the former Badger Ammunitions plant, Hocak Nation Environmental Services Program Manager Randy Poelma, walks the prairie collecting seeds.

Poelma was not alone. Joined by several Sauk County citizens, the morning served as a hands-on learning experience for a few that braved the cold.

Poelma oversees different environmental programs for the Nation, including the Water Quality Wetlands Program, Air Quality Program, Invasive Species, Stormwater, and all the permitting. He also is the project lead for the restoration project at Maa Wakacak.

“What we are trying to do here, after the last glacier converted what used to be spruce-tamarack forest and grass prairie, is trying to bring that back. It was lost and taken from the Hocak people and became an ammunition plant. We are trying to heal it by restoring it back to a tall grass prairie. A lot of the work in that, is to remove a lot of the invasive species that were out here. There’s a lot of Autumn Olive and Bush Honeysuckle plants, that are not native to Wisconsin but became established for different reasons,” Poelma said.

The state used to plant Autumn Olive as a wildlife species because it is conducive to wildlife. However, it quickly became invasive and took over and displaced the native flora.

Poelma said that the Nation has been removing it and putting fire back into the community. “Whether it was the Natives putting fire on the land intentionally to get cover for wildlife or it could have been natural lightning strikes that caused fire. But this whole glacial out-wash plain would have been tall grass prairie that would have had fire on it pretty frequently. That fire would have actually ran all the way to the north. We are looking at the Baraboo Hills which is an ancient mountain range. Today, we see it as all woods and covered with trees, but historically that would have been a much more open area.”

Poelma stressed that part the Nation’s work at Maa Wakacak, is not only to restore the prairie, but also restore a transition from the prairie on the glacial out-wash plain to the slope, the Baraboo Hills, and ultimately create and nurture an oak-savanna type system.

Sauk County resident Mike Putnam and his daughter Ava joined Poelma and others, to help gather seeds for a later planting, and felt it was how they could show support for the Day of Restoration.

“I heard about it by word of mouth. I’ve been with the Sauk Prairie Conservation Alliance for over 20 years as a volunteer. I keep track of when they have work days out here and saw that this one corresponded with Indigenous People’s Day. I thought this would be a good chance to be able to come out and do two good things at one time,” Putnam said. Ava added, “I think it’s important,” and acknowledging she is interested in land Conservation.

Also, among those collecting seeds were Rob Nurre, a landscape historian and current Man Mound custodian, whose work focuses on the interactions of natural and cultural history, and Mary Mjelde a Sauk Prairie teacher who also is involved with the Indigenous Students group at Baraboo High School.

“This is the first event of the first Sauk County Indigenous People’s Day. A number of us got together last fall and worked hard to come up with this idea of Indigenous People’s Day. It’s a chance for everyone in this county to understand that the indigenous people are a huge part of the past, the present, and the future of Sauk County. Sauk County is named for the indigenous people, the Sauk, who lived in this area in the mid-1700’s for about 50 years. This is Ho-Chunk traditional land. The Sauk were one of the many tribes that were being pushed around by the Europeans who started on the east coast and started the idea of pushing people around. The Sauk were one of the people who were pushed around, but made a huge settlement where Sauk Prairie and Prairie du Sac are today. That’s how the name Sauk gets attached to this county, even though it’s Ho-Chunk Homeland. As we were beginning to think of how to do this Indigenous People’s Day,” Nurre said.

He said that some residents of Sauk county wanted to do more than just a one day talk with the county board and the President of the Hocak Nation saying some good words.

“We wanted to get people involved. This is one of the things we came up with, this first day being a day of restoration. How do we, all of us whether we are European descent or Indigenous descent, how do we come together to help undo some of the damage that the European’s have done to this land,” Nurre said, and pointed out that Maa Wakacak is a great place to do what they can to facilitate restoration for this land.

With Mary Mjelde’s role as an educator, she saw the Day of Restoration as a continuation of her education on the indigenous people of Sauk county, namely the Hocak.

“Almost two years ago, halfway through the school year, I was put into the advisor of Indigenous Students group in the High School. We were formally recognized last year. I was the advisor of Indigenous Students United. It was a place where our indigenous students could come together and talk about issues that are important to them, what we could do to help support their culture within the Baraboo School District. We were able to go to the Unity Conference, which is where I got to meet Kristin White Eagle. Through working with her to get us to Arizona for that conference, she told me about this event that was coming up and got me involved from a school district standpoint. Although now I am teaching in Sauk Prairie, I didn’t want to give up that spot. I stayed involved with them, trying to figure out how to get more students involved with volunteering and coming out and being part of the events of this weekend.”

Mjelde said she has learned a lot about the Hocak over the last year and a half, and remarked “what a neat group of people they are, and their prospective on how things are going in the schools.” She also stated it was neat to be an advocate to help them feel loved in their culture.

The mural

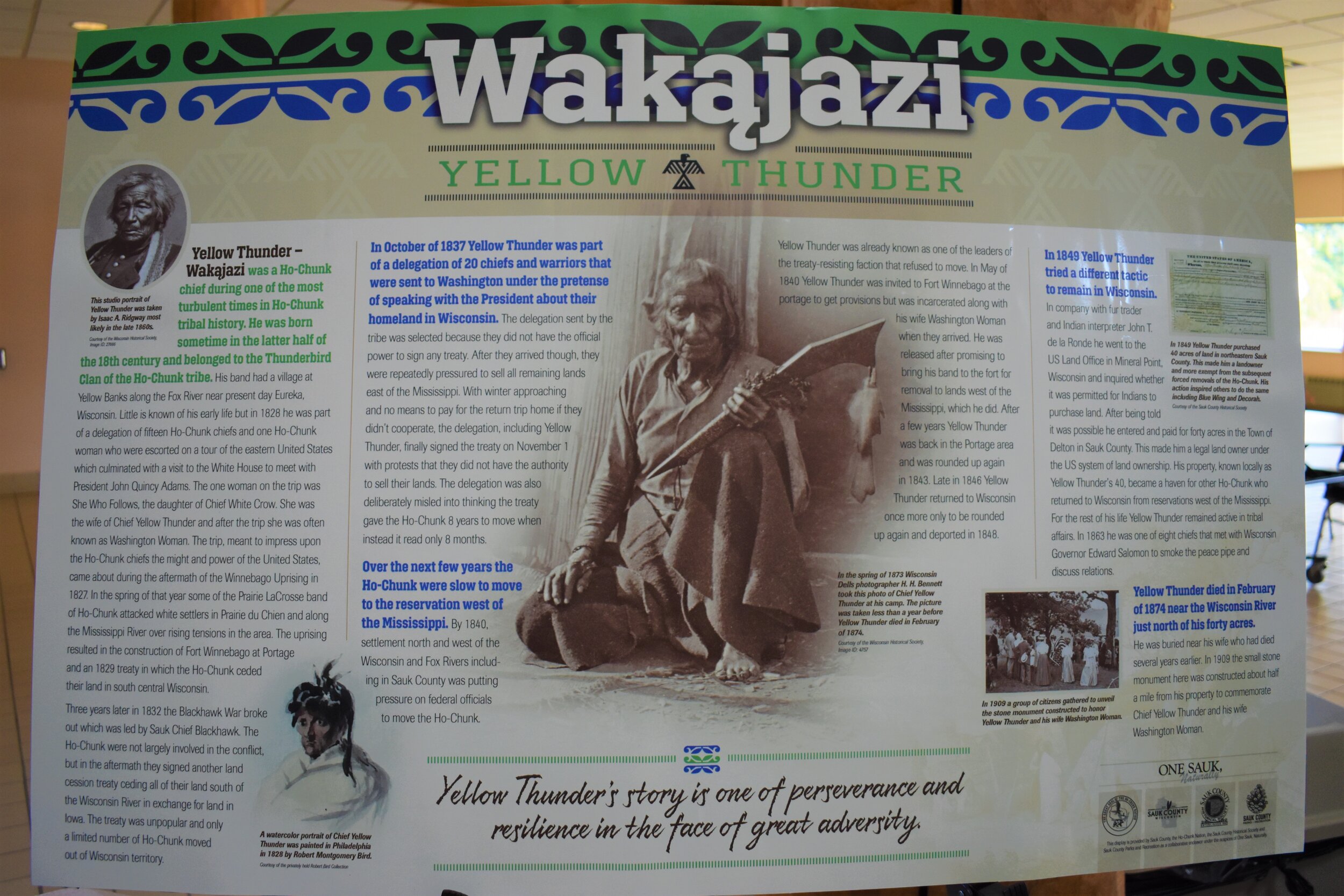

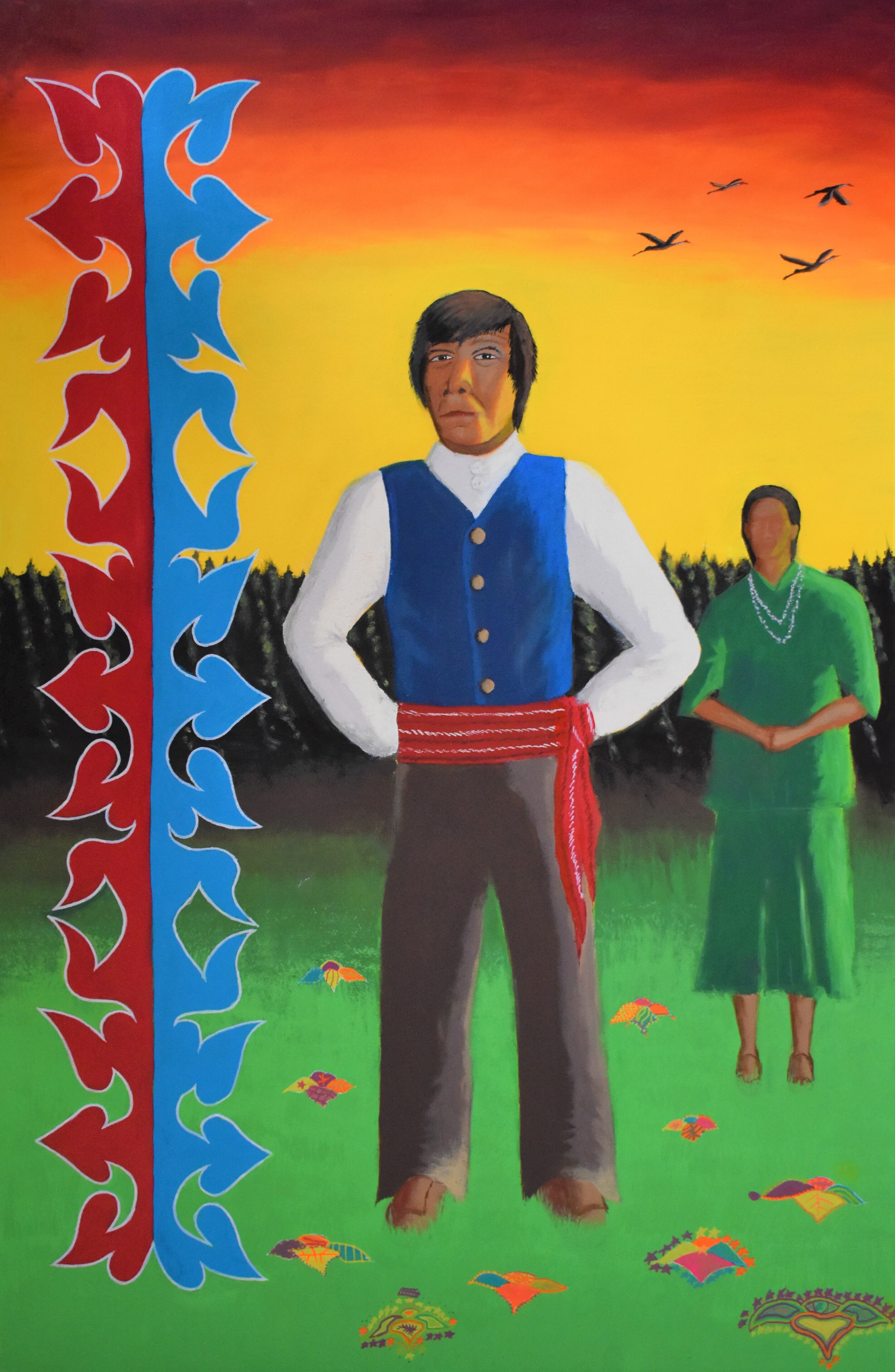

As part of the day of Restoration, the Little Eagle Arts Foundation enlisted the help of Hocak artist Kelly Logan, commissioning Logan to paint a mural of the great War Chief Wakajazi (Yellow Thunder). In the early 1800’s Wakajazi legally purchased a 40-acre plot of land, making way for Hocaks to return to Wisconsin, after a succession of removals by the United States government.

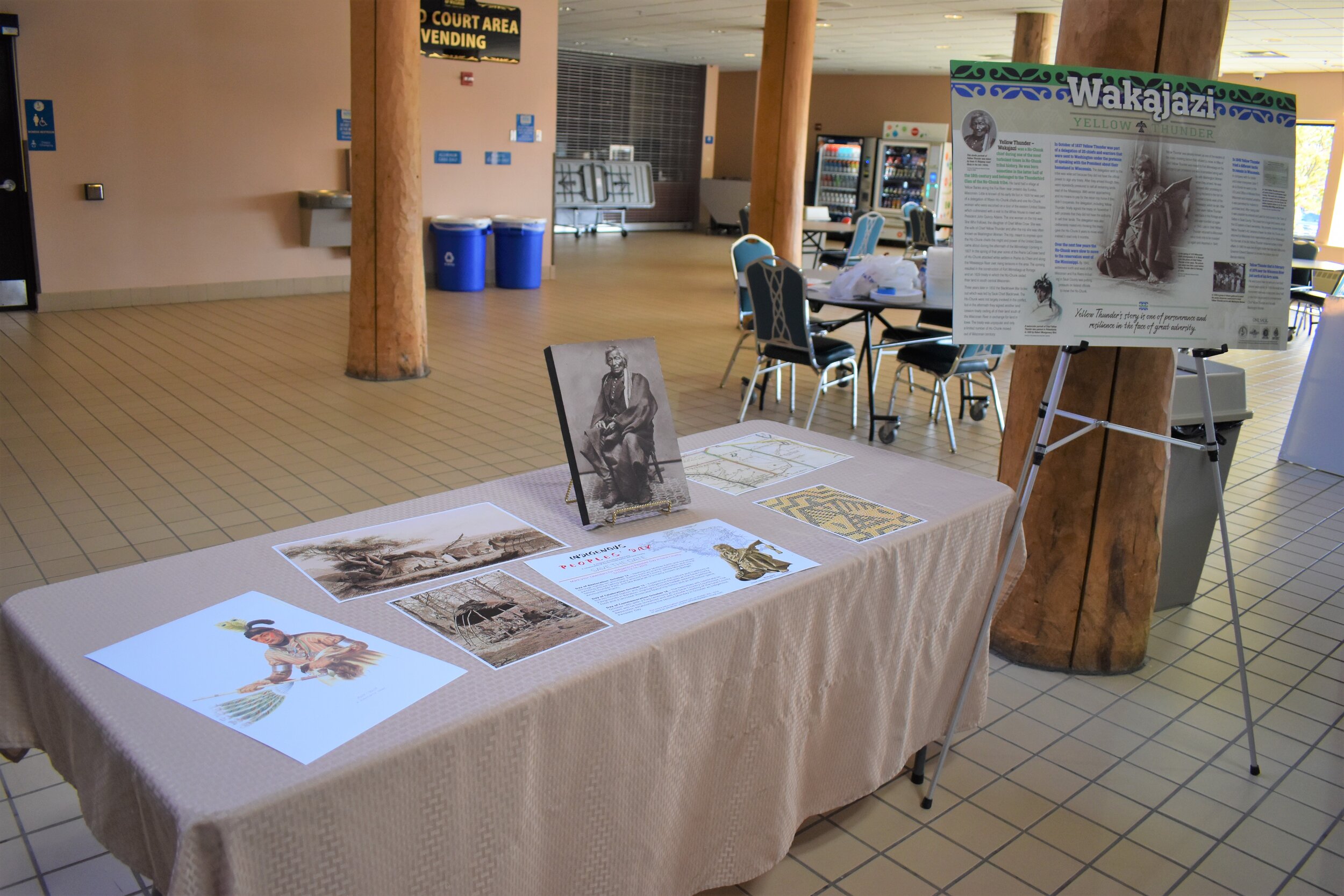

Logan displayed his mural and invited the public to add to it at the Hocak Wanaįšgųnį Hocira (House of Wellness), located just Northeast of Ho-Chunk Gaming Wisconsin Dells.

Visitors to the mural project, Maple and Sylvia, with their mother Leslie Schroeder alongside, added their touch to Logan’s mural.

On the mural Maple said, “I like it. I kind of like the eye too because it looks like it’s looking at you. I’m afraid of how to put stuff and how it’s going to look because I’m not sure how the green is going to turn out against it.” On Indigenous People’s Day, she shared, “It’s the first time I’ve ever heard of it, so I don’t really know what to think, but I like it and I like doing this.”

Her sister Sylvia added, “I like it, but I’m very surprised about these markers that paint,” she said with a smile.

Paul Wolter, Executive Director of the Sauk County Historical Society, greeted guests and offered a brief history on the Yellow Thunder Memorial located on Hwy A North of Baraboo.

“The memorial was developed and constructed by the Historical Society in 1909 to honor Chief Yellow Thunder’s Legacy. That was really great, but the signage is non-existent. For the first time since 1909, there will be an interpretive panel there that has pictures and full text of his story. We set up a temporary installation of it now, and as it gets around, it will be corrected as there are a few commas missing and things like that,” Wolter said.

Wolter said the historical society was invited to be on the planning committee for Indigenous People’s Day, and shared that their inclusion came up when Little Eagle Arts Foundation founder Melanie Tallmadge-Sainz spoke with Hocak elders.

“They really wanted Chief Yellow Thunder included in this whole event. They particularly wanted his image to be on the poster on the website,” Wolters said.

That brought up having an event at Yellow Thunder the site, Wolters said, and noted that some of the early discussions in planning included having some of the art piece that the community could help with, and that jelled around having an image of Chief Yellow Thunder painted.

The good news is that the interpretive panel is up at the site on Hwy A, and anyone stopping there now, will be able to learn more about his story.

“The mural, we hope, will travel around the county, along with the traveling version of the panel telling Chief Yellow Thunder’s story. I think that will be great in educating people in that the Ho-Chunk have always been here. Even though they were forcibly removed up to 10 or 11 times, there was always a remnant of them here in Wisconsin and Chief Yellow Thunder himself walked back at least four times several hundred miles and beating the soldiers that escorted him away and coming back. He eventually bought 40-acres in 1849, making him a legal landowner under the white system, and then he was less-likely to be deported. We’re not sure if he ever was deported after that.” Wolters said.

The 40-acre plot became kind of a haven for local Ho-Chunk, that would see some Hocak live there. Wolters said, “There’s times there would be pow wows and events where as many as 1200 to 1500 Ho-Chunk would be on that site at one time, which is a substantial number given that the current tribal membership is about 6,000, I think. Himself and Chief Dandy were two of the top leaders in the resistance movement and were constantly coming back to Wisconsin or staying here. It’s great that his story is going to be told, and this being the day of restoration, we feel that this is restoring that legacy of Chief Yellow Thunder to the public’s attention.”

Mural artist Kelly Logan, said he was pleased to be a part of the Day of Restoration. “Melanie came to me. She works with the Historical Society. Her and I did a few paintings and asked she me if I could do one. I said yes, I would be more than happy to paint him. I’ve never really done a full mural, so I was really excited to do it for the area and the Historical Society.

With a grin, Logan said, “I used to do graffiti in High School for a dollar and lunch tickets. Then, I went to college, did a little commercial art, and then I just stopped. About 3 maybe 4 years ago, I decided I wanted to draw again. I never could put colors into anything, I did mainly pencil and marker-simple-drawings. Then I started doing color and it turned out really good, and now that’s what I’m known for.”

With only two photos of Wakajazi as an elder for Logan to go by, his challenge to depict him in his younger years would be a challenge. Referring to those photos he said, “As one person said earlier, he looks like he’s worn down, and I didn’t want that image. I had to come up with the two pictures there are of Yellow and maybe his bone structure. I wanted him to look younger, vibrant. His wife is on there, but there is no picture of her or recording of her of how she looked or anything. I kinda, more or less, painted her face on there. Yellow Thunder traveled to Washington DC a few times and she went with him. She is, I think, of the Sioux people. She was always there for him, with him. It’s a simple Wisconsin sunrise on one of the tree lines. My girlfriend said it was kind of plain in that one corner, so I added some cranes because of the Crane Foundation in the area. I thought it would be a good representation for them as we try to keep that species going in the area. Of course, there’s the applique that I designed. Again, I don’t really draw or paint people. I usually do floral or geometrical designs.”

Acknowledging that painting is not his usual medium in art, Logan stated he’s glad he painted the mural and is very happy with how it turned out. “I think that’s how he might have looked at a younger age.”

The Savanna

With Sauk county’s historic landscape made up of prairie, oak-savannas were also prevalent.

For those that might not know, an oak savanna is a lightly forested grassland, where oaks are the dominant trees.

Oak-savannas were part of the landscape the Hocak would have lived in and near before European settlement, and having a sacred connection to Maa (Earth) important to them. These savannas have become rare and endangered over the years, making them a prime candidate for conservation and restoration respectively.

Sauk County Parks and Recreation Manager, Matt Stieve, led a tour of a savanna he currently is conserving and maintaining at White Mound County Park, located in Hill Point, Wisconsin.

To clear a popular misconception that the park has ancient Native American mounds, Stieve explained. “Individuals would dig rocks out of the side hill and cook them down in kilns to extract the lime from the stone. In a lot of the old homes in Wisconsin, the foundations if you see, they are made out of stones, it was probably made out of this limestone mortar. They would cook these rocks down and bake these rocks right down to a powder, which would release the carbon and leave the lime. At the time, the trees had been harvested off of these side hills. The hillsides were pretty naked not having any trees on them. With all of these little kilns all along the hillsides, the lime that was mixed with the ashes was no good, so they would discard that out the door which made the top of these hillsides all white from the ash. That’s how it got the name White Mound.

Stieve said the oak-savanna project that he is working on at White Mound though small, has been ongoing over the last 3 or 4 years. “It still has trees that didn’t get harvested in the late 1800’s, early 1900’s. There are some neat old oak trees. It’s an ideal setting for one. We’ve got the prairie on one side, and its accessible for people to walk to from our campground. People get to see what it looked like. Now, it’s just an oak-savanna remnant, a good oak-savanna would be 100-200,000 acres.”

Oak-savannas are probably the most ecologically rare plant community in the world he noted. “Oak-savannas are exceedingly rare, they used to be very abundant in the United States. At one time, I think it was estimated that there were 50 million acres of oak-savannas. I don’t know how many acres of quality oak-savannas are left, but most of what is left are inferior or remnants of oak-savannas.”

With the best way to manage an oak-savanna without a doubt is with fire, and Stieve said that the savanna remnant at White Mound is an ideal place to do a burn.

“We’ve got the lake over here, a prairie over here, so it’s a pretty manageable way to do a burn,” he said.

While some prescribed burns are difficult, he stated that doing a prescribed burn at the park is easier than most because of the topography.

“We can’t burn as much or as hot as we used to, so I go in there and manually remove some of the maple trees. It’s mostly maples that we are going after because they are quite prolific,” Stieve said.

With the oak-savanna a continuous maintenance project, Stieve is dedicated to its restoration. “I just want it so people can see what they are missing or what there was. You walk through that little trail at the top of the hill, and you can see what’s going on. It’s a lot of oak trees with a lot of herbaceous plants coming up. I’m just trying to have a little slice of an oak-savanna in the park so people have something to look at.”

Editor’s note: To be continued with an article, ‘A Day of Celebration’.